31st July - No Letter

Location: Ireland - Tipperary Barracks

The War Office sent a telegram to Poppy which arrived at The Hall in Welwyn on the 31st July. Poppy was still in London and as Peggy didn’t know her number she must have posted the telegram to her. Pencilled on top:

’sorry could not phone it as don’t know yr No Pegg’

Waterloo Rd OHMS Priority

To Mrs C Lucas The Hall Welwyn Herts

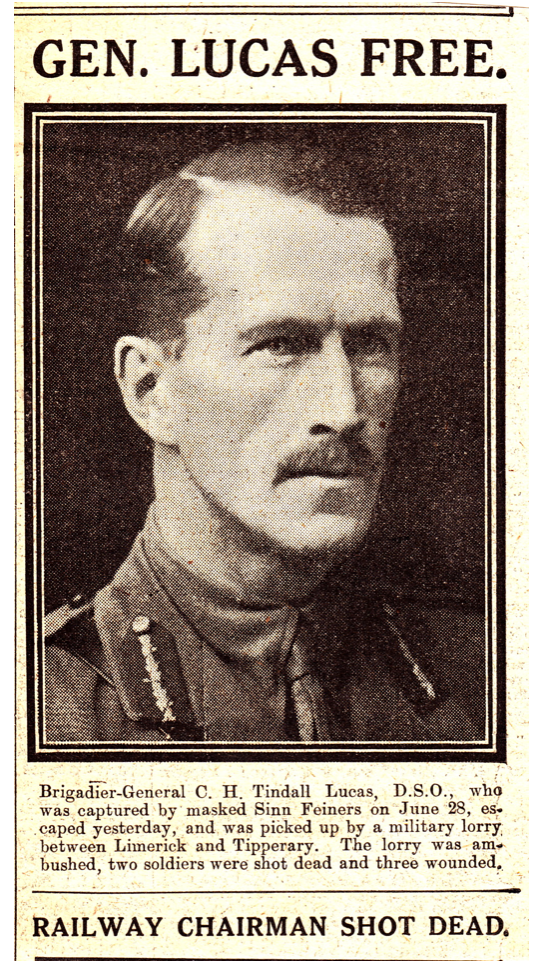

73 cas aaa beg to inform you report received as follows Dublin Castle to Irish office dated 30th July 9.45pm begins police at Limerick telephone message received [here] but General Lucas escaped from his place of consignment near Newcastle West Limerick this morning and was picked up by a military mail motor car with a despatch driver in front aaa the car was subsequently attacked by a party of Sinn feiners and two soldiers shot dead aaa General Lucas burst a blood vessel in escaping aaa a second military car came on the scene and saved the situation aaa the real facts not yet ascertained aaa police at Tipperary wire General Lucas now in Tipperary aaa he looks somewhat fatigued after a hard night but otherwise is well he is not confined to bed message ends Military Sec. Comorale [?] House War Office

Telegram dated 31 July 20

Poppy must have been relieved to have got this eventually. She must have felt quite left out as the Lucas family took centre stage and she became an after thought when it came to communicating with her. You would have thought that after a month of CHTL’s imprisonment, the family would have had a phone number for Poppy to keep her up-to-date with what they found out! They probably meant well, but could be quite over-powering and bossy!

Press Statement

It was in Fermoy that CHTL’s story was leaked to the press. He himself, aware of what had happened to Kelly and probably under strict instructions to keep quiet, did not speak directly to the journalists. He had told his story to his friends and maybe with a nod and a wink from him, they related the tale:

GENERAL LUCAS

DESCRIBES HIS IMPRISONMENT And Pays Tribute to his Guards

‘‘Had the Time of his Life.’’

An inquiry has been held at Fermoy into the circumstances attending the capture of Brigadier General Lucas, who was taken by Irish Volunteers while he was fishing in the Blackwater in June. The inquiry has concluded, but no details of the proceedings have yet been made public. It is, however, established that General Lucas’s place of captivity was changed every three or four days.

He was guarded continuously either by a brigade or a battalion- commander of the Irish Volunteers. He has no knowledge of the whereabouts of his final prison, but on the day of his arrival there his escort was busily engaged in organising, by a pure coincidence, the attack on the military motor mail lorry at Oola. While in this affair, the General discovered that the bars of the window of his prison were by no means so secure as they were thought to be, and after working steadily at joints in the concrete he was able to remove them and so escape. It was two o’clock in the morning when he scrambled down the wall, injuring himself in the descent, and for five hours he wandered across country in the pouring rain until finally he reached the village of New Pallas.

From here General Lucas boarded the mail lorry, which his captors had arranged to ambush, and when it was held up he seized a rifle and took an active part in the defences, being wounded by a bullet searing his forehead. For two days he remained in Tipperary barrack while the Irish government threw a screen of secrecy about him. The General desired to go to England to see his wife, who is in a nursing home, but the formalities of the military command must be obeyed, and so he languished at Fermoy simply because it is ‘‘a way they have in the army.’’

General Lucas has no complaint to make about the manner of his captivity. Always, he says, he was treated as a gentleman by gentlemen. Not for a single moment was he made to feel his position as a prisoner of war. The monotony of his captivity was relieved by books and games, and his captors joined him in fishing and shooting expeditions. As a matter of fact, General Lucas frankly declares that he had the time of his life, and his only trouble was the knowledge that his family would be anxious over his welfare. Again he admits that his guards assured him that his wife knew he was safe. ‘‘My captors were delightful people,’’ says General Lucas, ‘‘Of course I escaped at the first opportunity, but I have no complaint to make I was not a prisoner so much as an unwilling guest.’’

Newspaper article reproduced p194 In the Shadow of Shanid: the Life of Captain Timothy Madigan by Tim Donnovan

The visible wound on his face made CHTL’s message of having no complaints about his captors even more powerful. He could so easily have changed his tune and felt anger at the IRA for the attack at Oola and the killing and wounding of soldiers. Notwithstanding this, CHTL stuck to his word of honour and would not let recent events cloud his original opinion of those who held him. As a soldier he knew that (unofficially) there was a war on and the attack was part of that conflict.

The press were eager to get the story. Everyone wanted to know 'General Lucas’s account'. Saying that he’d had ’the time of his life’, was not expected but it made the story even more intriguing and CHTL more the ’hero’ and not the ’victim’.

CHTL took a big risk in leaking his story to the press, especially as he knew that Churchill wanted him court-martialled and what had happened to Sherwood-Kelly after he spoke to the press. CHTL cleverly got his story across without incriminating himself. By now CHTL was becoming very impatient: he just wanted to get back home to Poppy and to meet his son for the first time. He was going to tell his story his way and not be influenced by the authorities, even though they didn’t want to hear that he had a good time and had no complaints to make about his captors.

Report on IRA

Following the euphoria of his escape CHTL had to face the music and report to his military superiors. He was on very sticky ground. With Churchill calling for him to be court-martialled, there was an urgent need for the errant general to give a good account of his months absence and to compensate his seniors for the embarrassment he had caused them with some useful information. He told it as he saw it. The British had to choose between another bloody extended war or negotiate some form of Home Rule as Lord Cecil, his MP whom he admired, advocated.

’After his escape General Lucas had made a report to his own authorities, a copy of which was secured by General Headquarters Intelligence. In this report he had included his impressions of I.R.A. organisations as he had seen it through contact with officers and men during the month he was a prisoner. He was impressed by their standards of discipline, determination and efficiency. In his opinion the British Forces in Ireland were confronted with a much graver military situation than was generally realised. He foresaw a long and bitter struggle, in which it would be necessary to employ much larger forces than those then garrisoning the country if the Army of the Republic was to be exterminated.

Extermination of the Irish armed forces, openly in the field, by midnight murder, or by shooting or hanging prisoners under the contorted legality of Martial Law, was in fact the policy decided upon by the British Cabinet. Voices which raised doubts of the efficiency of such a policy were ignored. In the House of Lords on 26th April Lord R. Cecil said:

“We are drifting through anarchy and humiliation to an Irish Republic... we will never settle the Irish question except with the wishes of the Irish people.”’

P81-82 No other Law, Florence O’Donoghue, ANVIL

Florence O'Donoghue (1895–18 December 1967) was an interesting character. In later life he became a historian and wrote the classic ‘No Other Law’ (the story of Liam Lynch the Irish Republican army, 1916-1923)

During the war of independence, Florence O'Donoghue was head of intelligence in the Cork No. 1 Brigade. He successfully recruited ‘agents’ who were working right in the heart of the British army’s HQ in Ireland.

One of O’Donoghue’s most important and valuable spies was Josephine Marchment who worked as a typist in the Victoria Barracks in Cork. Josephine's first husband was killed in the First World War. Her parents in law managed to get custody of her eldest son and took him to live with them in Wales. Distraught, Josephine turned to the local IRA in Cork. They managed to go to Wales, find Josephine’s son and bring him back to Cork. O’Donoghue was one of those who organised this. At the end of the war Josephine and O’Donoghue were married.

Being so grateful to the IRA for bringing her son back to her, Josephine decided to work for the cause. She was head female clerk at the 6th Division Headquarters at Victoria Barracks, Cork and passed on secret British Army correspondence to O'Donoghue. One of Josephine’s most important bosses was General Strickland, CHTL’s immediate superior. There would have been very little that the IRA didn't know about Brig general Lucas. It was probably Josephine who got hold of a copy of CHTL’s Report.

Court Martial

There were a lot of political murmurings behind closed doors as to what to do about CHTL. Churchill wanted him court-martialled but others didn’t see him as having caused the situation but more as a victim of circumstances beyond his control. The Brigadier General’s outspoken testimony to the finer qualities of his captors rankled with those in parliament who didn’t want Sinn Fein portrayed in anything but a bad light.

Wilson’s diary mentions a conversation that he had with Lord Duncannon on Ireland, sometime between 17th and 28th July 1920. He told Duncannon that if he was in the House of Commons he would:

“march down to Lloyd George and say: “You have two courses open to you. One is to clear out of Ireland and the other is to knock Sinn Fein on the head. But, before you do this latter, you must have England on your side, and therefore you must go stumping the country explaining what Sinn Fein means. If you get England on your side-and you can-there is nothing you can’t do. If you don’t then there is nothing that you can do.”

The Military Correspondence of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson 1918-1922 edited by Keith Jeffery Entry 135

So CHTL coming out and saying that he was ‘treated as a gentleman by gentlemen’ and was held by ‘delightful people’ would not have helped to get England ‘on their side’ against Sinn Fein! He needed to have come out saying that they were evil people who were a threat to Britain and who needed to be eradicated, to have redeemed his politically embarrassing capture and given the government factions aligned to Wilson the green light to send in the troops ‘to knock Sinn Fein on the head’.

CHTL’s daughter, Anne, said that CHTL always said what he thought - it was how she and her brothers were brought up. CHTL wasn’t someone to toe the party line. In the letters to Poppy leading up to their wedding CHTL got very frustrated with his leave being postponed and he wrote, 'If it is delayed any longer I shall get very subordinate and probably be kicked out of the service'. The Quaker non-conformist genes came into the picture again – the Lucas family had generations of people who stood up and said what they believed to be right in spite of any unfavourable consequences or being in a minority with the ‘authorities’ disapproving.

Maybe certain sections of the British government had been secretly hoping that CHTL would have been killed by Sinn Fein as that would have got England ‘on their side’ to send in the troops?

Sherwood Kelly, less than a year earlier, had been conveniently disposed of on the charge of having spoken to the press without permission and it would have been very easy to have used the same technicality to have ’punished’ CHTL. Kelly may well have called on CHTL to stand as a character reference so Lucas would have been already marked as a ’subversive’ in Churchill’s eyes.

However CHTL had the huge advantage that, unlike Kelly, the vast majority of his commanding officers thought highly of him and liked him! His years of charm and working hard to keep up with friends may have paid off at his most critical hour. He had earned the respect of those he’d served under by his determined hard work and undoubtable achievements which had greatly helped towards the success of those operations he was involved with.

Churchill thought that Lucas deserved a court martial for the ‘crime’ of going fishing, allowing himself to be captured and not fighting back and taking a load of Sinn Féiners down with him. Churchill was not shy of sacrificing lives for political/military ends. Gallipoli was one such case: “The price to be paid in taking Gallipoli would no doubt be heavy,” he wrote, “but there would be no more war with Turkey. A good army of 50,000 and sea-power—that is the end of the Turkish menace.” Russia was another where Sherwood Kelly objected to the waste of soldiers lives. He’d made it very clear that he was willing to sacrifice Lucas’ life for military/political gain in Ireland.

There may have been a little envy: In November 1916, when Churchill arrived in France, following the Gallipoli disaster, he had expected to be given a Brigade and Brigadier General's rank, but Prime Minister Asquith vetoed him being given a high command. Instead Churchill was given the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, with command of a battalion of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers. He proved to be a brave and popular officer amongst his men. CHTL was someone who had achieved the rank that Churchill had wanted and yet Churchill didn’t think Lucas worthy of it.

When it came to court martial: Brig General Dyer escaped as he had the public behind him and possibly military men were uneasy about setting a precedent in case they found themselves in a similar position. Colonel Sherwood Kelly, was an awkward character and probably CHTL was the only senior officer willing to stick their necks out for him, so he went down. However Brig General Lucas was in a different category.

CHTL had been mentioned in dispatches ten times, he was not some maverick officer who could be quietly put away. His list of referees, which contained the names of many of the most prominent generals of the day, prove that CHTL was someone who was held in high regard. Churchill was possibly not amongst the military’s favourite people, with many remembering the disaster of Gallipoli, and given the choice the army would side with their own.